Shortcomings in Healthcare for Pregnant Incarcerated Women

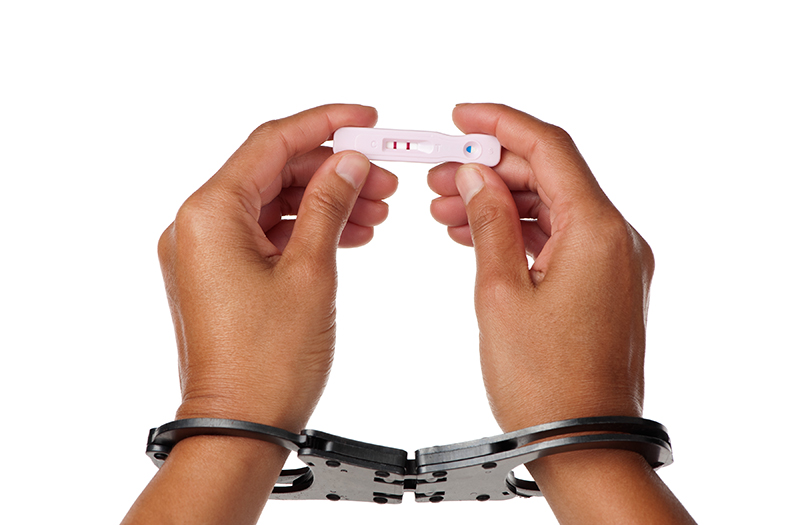

Pregnant adult and adolescent women who have entered the United States criminal justice system are an extremely vulnerable population. Many of their pregnancies are high-risk due to lack of access to adequate care and prenatal nutrition before, during, and after incarceration. This lack of access to appropriate care is often further exacerbated by domestic violence, mental illness, substance abuse, and pregnancy during adolescent years. The United States criminal justice system has recommended—but has largely failed to enact—guidelines for adequate prenatal and perinatal care for pregnant incarcerated women.

The Statistics:

In 2015, it was estimated that female arrests comprised around 27% of total arrests in the United States. Most of these arrests were for non-violent crimes, like larceny-theft and property crime. In 2016, there were more than 110,000 women held in federal and state prisons in the United States. Most of these women were committed for non-violent crimes such as drug and property offenses.1

In general, female adolescents involved in juvenile arrests have also been implicated in a larger proportion of non-violent crimes, including larceny-theft, liquor law violations, simple assault, and disorderly conduct but have accounted for only a small proportion of violent crimes. In 2015, juvenile residential facilities held approximately 48,000 youth offenders. Females accounted for 15% of this population.2

In 2017, approximately 194,377 babies were born to teen mothers aged 15 - 19, comprising a birth rate of 18.8 per 1000 teens. There is no data on the corresponding incarcerated adolescent population, but a national survey involving 261 correctional facilities estimated housing between 1 and 5 pregnant girls every day. It has also been estimated that around 3 - 4% of incarcerated adult women are pregnant at the time of commitment, and 75% of incarcerated adult women are of childbearing age.3

How does healthcare fall short for this special population?

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, thirty-eight states have failed to enact adequate healthcare policies, if any at all, for incarcerated pregnant women.4 Forty one states have not instituted any standards for prenatal nutrition and thus have failed to provide adequate nutrition to their incarcerated pregnant women. Prenatal nutrition is extremely important for preventing serious birth defects and developmental issues in the fetus and for preventing nutritional deficiencies in the mother.5 Therefore, not adequately addressing the nutritional needs of pregnant incarcerated women can be detrimental not just to the women, but also to the developing fetus who will then go on to become members of our society.

In 2008, the Federal Bureau of Prisons formally ended the use of shackles on pregnant inmates. The American Correctional Association approved similar standards that same year. Similarly, the National Commission on Correctional Healthcare adopted the same stance opposing the use of shackles on pregnant inmates in 2010. However, these policies recommending the prohibition of restraints on pregnant inmates are voluntary and have not been mandated. Thus, 36 states have failed to stop the use of restraints on incarcerated pregnant women. The use of restraints interferes with normal labor and delivery and has been shown to interfere with adequate diagnosis and treatment during prenatal care.4

What can we do?

According to the Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, legislative bodies at both the state and federal levels as well as healthcare professionals involved in prenatal and perinatal care may be the most effective in improving healthcare standards for incarcerated women.4 The following is a list of proposed avenues for improvement:

1. Obstetrician-gynecologists caring for incarcerated women should restrict shackling during care to high risk inmates or those incarcerated for violent crimes.

2. Obstetrician-gynecologists caring for incarcerated women should continue to provide care after their release from correctional facilities.

3. Federal and state governments should enact mandated policies that support the provision of adequate prenatal nutrition for incarcerated women.

4. Federal and state governments should enact mandated policies that restrict the use of restraints on low risk incarcerated women.

5. Correctional facilities should provide prenatal care training for correctional officers.

These changes are crucial in order for us to provide adequate care to one of the most vulnerable populations in our society and to ensure a healthier population in the future.

Author bio:

.jpg)

Alexandria Lee

Alexandria Lee is a 2nd year medical student at Loma Linda University School of Medicine. She graduated from UCLA with a degree in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and has always been interested in intersectionality in medicine. When she’s not studying, she can be found at a coffee shop in LA.

References

- https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2015/crime-in-the-u.s.-2015/tables/table-42

- https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/251486.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6459671/

- https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Health-Care-for-Pregnant-and-Postpartum-Incarcerated-Women-and-Adolescent-Females?IsMobileSet=false

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6459671/