Building Municipal Health, One Tree at a Time

The built environment can best be described as the way we design and physically build our communities and neighborhoods. City policies that shape this environment may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of population health. However, when we consider that 90 percent of health occurs outside of a clinical setting 1, it is no surprise that these policies have the opportunity to greatly influence health and well-being. There is a good reason why the built environment is referred to as health policy in concrete 2.

For example, having more city trees lining the streets can 3, 4:

- Improve local and regional air quality

- Increase property values

- Reduce heat island effects and energy use

- Create more aesthetically pleasing and memorable spaces.

- Increase auto, pedestrian and bicycle safety

The presence of trees also has many positive health effects such as 5-8:

- Improved mental health

- Reduced blood pressure and anxiety

- Lower likelihood of asthma

- Reduced mortality and physician-assessed-morbidity

- Greater participation in physical activity.

Do Trees Grow Money?

Trees lining California’s streets provide over $1 billion in continual benefits to the State and its residents through improved air quality, increased property value, reduced energy use, etc.9. This value is generated even without accounting for numerous health benefits associated with planting more tress. Perhaps money really does grow on trees!

Similar to preventive health care, studies show that when cities take a proactive approach to street tree care, they have lower maintenance costs with greater benefit than cities that neglect timely tree care.10.

Given the generous economic and public health advantages provided by street trees, why don’t we see more cities investing in their care?

DID YOU KNOW?

For every $1 invested in tree planting or maintenance, communities see a $5.82 return, on average.9

Case Study: Redlands and Loma Linda

While neighboring Redlands and Loma Linda share a similarly diverse population, socioeconomic demographics, geography and climate, their built environment policies are significantly different. Figure 1 vividly illustrates the two cities’ diverging approaches to street trees.

Figure 1. Contrasting tree cover in residential areas for Loma Linda (left) and Redlands (right).

The Tale of Redlands

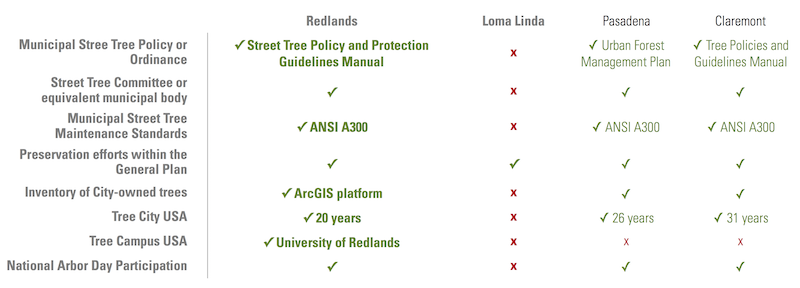

The City of Redlands is renowned for its quality image and takes pride in its architectural, cultural, and agrarian heritage. Street trees in Redlands date back to when streets were initially laid out in 1881 by founders Judson and Brown. Recognizing the important value that trees provide to the City’s quality of life and the meaningful heritage that they represent, Redlands has taken steps to ensure that tree care is based on best available practices. Like the cities of Pasadena and Claremont, Redlands has prioritized tree care efforts throughout its municipal structure shown in Table 1 below. Today, approximately 32,900 street trees are shading Redlands’ public roadways and sidewalks, through its continuing culture and commitment to tree care 11.

Table 1: Municipal commitment to street tree care

The Tale of Loma Linda

Strongly rooted in its Seventh-day Adventist faith tradition, the City of Loma Linda developed within the realm of health care and health professional education, with its municipal body emphasizing a commitment to open spaces and natural resource preservation. Throughout Loma Linda’s founding years in the early 20th century, many mature tree-lined and canopied roads led to the original Sanitarium on the present day Loma Linda University Health (LLUH) campus 12.

In recent decades however, there has been an observed tree canopy loss potentially due to poor trimming methods leading to frequent tree removal. This is most noticeable on major thoroughfares within LLUH campus and town core as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of street tree loss in central Loma Linda along Anderson Street, 2006 (left) and 2015 (right) 12.

Despite LLUH’s historical drivers for preventive health, a heritage of health care, wellness and the connection to nature and open spaces, Loma Linda is not currently in a position to strategically plant and maintain its street trees based on best practices. While there may be cultural aspirations for a greener Loma Linda as was highlighted during community workshops in 2012, local leadership has not been able to carry out supporting efforts or policies.

In contrast, as a measure of its commitment to tree care, the City of Redlands has received its 20th annual Tree City USA designation in April of this year. University of Redlands has also been named as a Tree Campus USA school – a designation given based on institutional commitment to tree preservation. Neither the City of Loma Linda nor LLUH have achieved these designations.

Policy and Culture

Both cities have room for improvement but it will take a more engaged leadership and strategic vision for Loma Linda to gain ground, if so desired. Culturally, both cities understand that there is a cost to alienating nature from places where we live, work, play and pray. Whether these cultural norms are robust enough to shape dedicated policy and engage leadership is something that remains to be seen.

Surely we do not enjoy spaces devoid of shade, comfort, visual appeal and safety. If we envision our towns as restorative environments, then we must be proactive in reaching a cultural and policy consensus towards a smarter built environment.

Andrejs Galenieks, MPH, MArch

Andrejs Galenieks, MPH, MArch, has a background in Public Health Policy and Architecture and Urban Planning and current works as a Health Policy Analyst at IHPL. Having worked in both fields, he hasa strong commitment and leadership to the intersection of the built environment and health.

For more information contact Andrejs at: [email protected].

- McGovern, L., G. Miller, and P. Hughes-Cromwick, Health Policy Brief: The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health Outcomes. Health Affairs, 2014.

- Jackson, D., Designing Healthy Communities. 2012, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/John Wiley & Sons. 230.

- Donovan, G.H. and D.T. Butry, Trees in the city: Valuing street trees in Portland, Oregon. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2010. 94(2): p. 77-83.

- Nowak, D.J., et al., Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States. Environmental Pollution, 2014. 193: p. 119-129.

- Bratman, G.N., The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2015(138): p. 41-50.

- Bratman, G.N., et al., Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015. 112(28): p. 8567-8572.

- Maas, J., Morbidity is related to a green living environment. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2009(63): p. 967-973.

- Kardan, O.e.a., Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Scientific Reports, 2015. 5(11610): p. 14.

- McPherson, G., N.v. Doorn, and J.d. Goede, Structure, function and value of street trees in California, USA. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2016. 17: p. 104-115.

- Hauer, R.J., J.M. Vogt, and B.C. Fischer, The Costs of Maintaining and Not Maintaining the Urban Forest: A Review of the Urban Forestry and Arboriculture Literature. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 2015. 41(6): p. 293-323.

- Redlands, C.o., Street Tree Policy and Protection Guidelines Manual, Q.o.L.-S.T. Committee, Editor. 2013, City of Redlands: Redlands, California.

- Park, D.E., The Mound City Chronicles - A Pictorial History of Loma Linda University a Health Sciences Instititution. 2005, Loma Linda, CA: Loma Linda Alumni.

Did you like this article? We want to hear from you! Leave your comments or questions in the space below.

Please note that the views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Loma Linda University Health or the Institute for Health Policy and Leadership.